Adapted from the published manuscirpt: Andreu, I. + , Falcones, B. + , Hurst, S., Chahare, N., Quiroga, X., Le Roux, A. L., … & Roca-Cusachs, P. (2021). The force loading rate drives cell mechanosensing through both reinforcement and cytoskeletal softening. Nature communications, 12(1), 1-12.

Introduction

Cells are constantly subjected to forces that play a crucial role in regulating various biological processes in both health and disease. Despite the importance of these forces, the fundamental mechanical variables that cells sense and respond to remain incompletely understood, and have been a subject of intense debate among researchers. In this study, we aim to shed light on the role of the loading rate in mechanosensing, investigating how cells respond to both directly applied forces and passive mechanical stimuli. We hypothesize that the loading rate triggers reinforcement at the sub-µm adhesion scale and cytoskeletal softening at the cell scale, which could have important implications for understanding mechanosensing mechanisms in various biological contexts.

Methods

To investigate the role of the loading rate in mechanosensing, we employed a multifaceted approach that combined experimental techniques and data analysis. First, we utilized an optical tweezers system adapted from a previous setup to precisely manipulate and measure forces exerted on cells. Next, we employed atomic force microscopy (AFM) to study the reinforcement at the sub-µm adhesion scale and cytoskeletal softening at the cell scale. To analyze the data obtained from these experiments, we developed a custom-made MATLAB program that allowed us to process and interpret the force and displacement signals. Finally, we conducted in vivo experiments using rat lungs to analyze YAP nuclear localization at different frequencies, providing insights into the physiological relevance of our findings.

Results

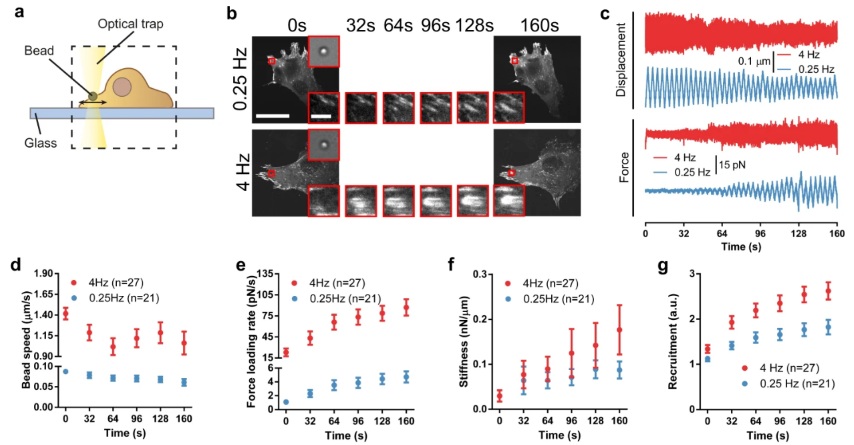

Our results demonstrate that force loading rates play a central role in driving mechanosensing by increasing reinforcement and adhesion growth at the local adhesion level, in a talin-dependent manner, as predicted by a molecular clutch model. Bead speeds and force loading rates were measured using respectively the displacement and force signals of the optical trap. Using a custom-made MATLAB program, each signal was detrended and then divided into linear segments of individual cycles and fitted to straight lines to obtain the slopes.

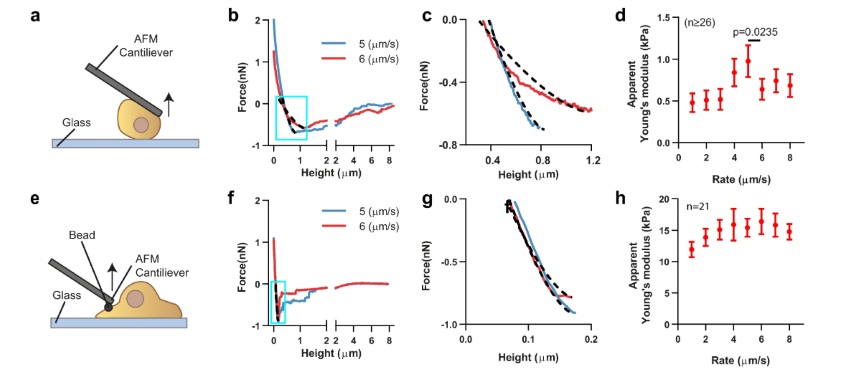

The maximum detachment force was determined by analyzing the retraction F–D curve. A MATLAB program was used to extract and analyze force-displacement curves from JPK data files. Forces were corrected as described in the literature76 by subtracting the baseline offset, i.e., the value obtained at the end of curves when cells were fully detached. We calculated apparent stiffness (Young’s modulus) by fitting retraction curves between the values of zero force and the maximum detachment force Fad, defined as the absolute value of the minimum of the curve. This corresponds to the part of the curve from the onset of cell stretching (positive force values at the beginning of curves correspond to cells still in compression) to the point at which cells start detaching. Curves were fitted to the Derjagin, Muller, Toropov (DMT) contact model, which considers the force-indentation relationship between a flat surface and a sphere, taking into account both elastic deformations and adhesion between the surfaces.

We found that when loading rates are too high, the cytoskeleton undergoes softening, which impairs mechanosensing. This softening event likely involves the disruption of actin filaments, as it was prevented by a drug that stabilizes them (Jasplakinolide). Our study also revealed a biphasic dependency of focal adhesions and YAP localization in response to different loading rates, highlighting the importance of both reinforcement and softening mechanisms in mechanosensing.

Conclusion

Our study provides a unifying mechanism to understand how cells respond to both directly applied forces and passive mechanical stimuli such as tissue rigidity or extracellular matrix (ECM) ligand distribution. It offers a comprehensive framework to understand how the seemingly opposed concepts of reinforcement and cytoskeletal softening are coupled to drive mechanosensing in different biological contexts. Potentially, this framework could be extended to explain mechanosensing mechanisms beyond focal adhesion formation and YAP, such as the actin-dependent nuclear localization of MRTF-A. In vivo, the wide range of loading rates observed in different contexts could be central to understanding how mechanosensing is regulated. Our findings may have important implications for various fields, including mechanobiology, tissue engineering, and cancer research, and could potentially contribute to the development of novel therapeutic strategies.