Adapted from the published manuscirpt: Andreu, I. + , Granero-Moya, I. + , Chahare, N. R., Clein, K., Jordàn, M. M., Beedle, A. E., … & Roca-Cusachs, P. (2022). Mechanical force application to the nucleus regulates nucleocytoplasmic transport. Nature Cell Biology.

Introduction

Mechanosensing, the process by which cells sense and respond to mechanical stimuli, plays a crucial role in numerous biological processes and has been linked to various health and disease states. Recent evidence suggests that the cell nucleus itself can act as a mechanosensor, with force applied to the nucleus influencing chromatin architecture, transcription machinery accessibility, and nucleoskeletal protein conformation, among other effects. In this article, we explore the intriguing hypothesis that nucleocytoplasmic transport, a fundamental cellular process, could be mechanosensitive in its own right, independent of specific signaling pathways. We investigate how nuclear force regulates both passive and facilitated diffusion, and how this may provide a general mechanism for controlling protein localization and transcription within cells. Our findings reveal a novel and potentially powerful avenue for understanding and manipulating cellular responses to mechanical stimuli in various pathological conditions and for designing artificial mechanosensitive transcription factors.

Methods

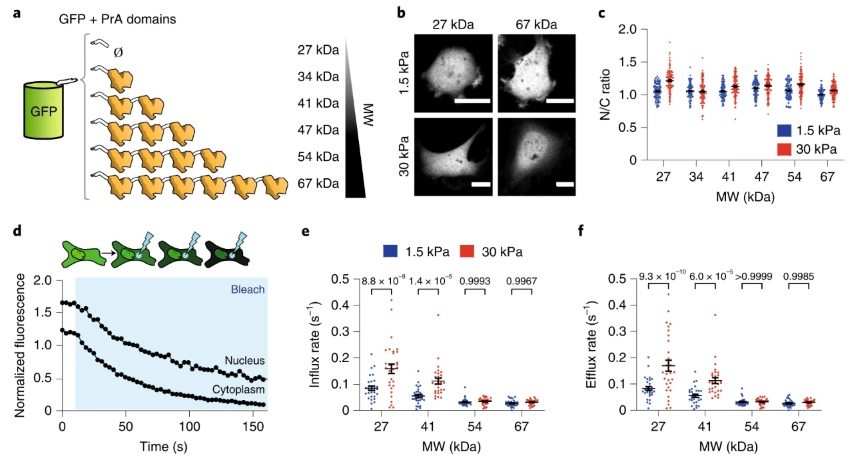

We used FLIP (Fluorescence Loss In Photobleaching) experiments to assess the influx and efflux rates of different protein constructs between the nucleus and cytoplasm. To model the FLIP data, we developed a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) that describes the change in protein concentration between the nucleus and cytoplasm. We assume that the proteins are unbound and mobile in each compartment and that during steady state, cells maintain a constant ratio (α) of protein concentration between the nucleus (n) and cytoplasm (c), and the flux between both compartments is equal. The boundary fluxes going in (Qi) and out (Qe) of the nucleus are proportional to the concentration of the compartment times a rate coefficient. Here, ke′ and ki′ are efflux and influx rate coefficients, respectively, and η′ is the bleaching rate.

We define normalized rates as ke=ke’/Vn, ki=ki’/Vn, η=η′/Vn, where Vn is the volume of the nucleus. By substituting ki, we get the following equations to solve ultimately:

\[{dN \over dt} = -(ke)n + (ke\alpha)c\] \[{dC \over dt} = +(\beta ke)n - (\beta ke\alpha + \beta \eta)c\]We then solve these equations numerically using the MATLAB function ode15s and fit them to the experimental data to obtain influx/efflux rates and bleaching rates.

For quantification of FLIP experiments, we followed the fluorescence intensities of three different regions, segmented manually: nucleus, cell, and background. We used a bleaching ROI of 17 × 17 (~12.9 μm²) pixels. The power of the laser used to bleach was adjusted to result in the same bleaching rate η. Cells with beaching rates above 0.12 were discarded.

The ROIs identified for nucleus and cytoplasm were narrow rings around the nucleus, either inside or outside of the nucleus. The average fluorescence intensity of these regions was used as a proxy for nuclear concentration (n) and cytoplasmic concentration (c). The intensities were corrected for background noise and normalized by the total integrated cell intensity.

Experimental data for n and c was used to solve Eqs. 1 and 2, as explained above. To calculate the ratio of N/C volume (β), we measured area ratios from images and converted this to volume ratios using the experimental correlation.

To solve for unknown variables, we used a curve fitting technique with a weighted least-square method. The objective function f is formulated as the sum of squares of residuals of model and experimental data. We used the fminsearch function of MATLAB to minimize f as a function of ODE parameters ke and η. For each iteration, nf and cf are calculated as a function of ke and η using the MATLAB ode15s solver. The resulting fitted rates showed more variability for conditions with fast rates than conditions with slow rates.

In conclusion, we used FLIP experiments and mathematical modeling to quantify the transport dynamics between the nucleus and cytoplasm. We found that the size of the nucleus is a key determinant of the transport dynamics between the nucleus and cytoplasm. Our results suggest that the transport dynamics between the nucleus and cytoplasm are regulated by the balance between passive diffusion and active transport. The actin cytoskeleton and the nuclear envelope play important roles in regulating the transport dynamics between the nucleus and cytoplasm. Our findings provide new insights into the regulation of nuclear-cytoplasmic transport and its implications for cellular function.

Results

Our results provide compelling evidence for the mechanosensitive nature of nucleocytoplasmic transport, with nuclear force affecting both passive and facilitated diffusion. Through a series of experiments, we systematically dissected the contributions of these two transport processes, revealing important insights into how nuclear force modulates protein localization and transcription.

For passively diffusing constructs, we found no significant mechanosensitivity in terms of concentration, but observed differences in diffusion kinetics. Nuclear influx and efflux rates increased with substrate stiffness, and this effect was more pronounced for molecules with low molecular weight and high diffusivity. This suggested that nuclear force weakens the permeability barrier of nuclear pore complexes (NPCs), with the effect being more substantial for smaller molecules.

In the case of facilitated diffusion, our data showed that force affects both import and export processes. We demonstrated that force-induced mechanical weakening of the NPC permeability barrier differentially impacts passive and facilitated diffusion, providing a means for force-induced nuclear or cytosolic localization of cargo.

Our findings also highlight the potential role of the LINC complex and the deformability of NPCs in mediating these mechanosensitive effects. However, several open questions remain, including the detailed molecular mechanisms underlying the weakening of the permeability barrier, the properties that confer mechanosensitivity to specific proteins, and the reasons why facilitated export is less affected than facilitated import.

Overall, our results offer a comprehensive understanding of the mechanosensitive nature of nucleocytoplasmic transport and pave the way for further exploration of mechanosensing in health and disease, as well as the development of innovative therapeutic strategies and artificial mechanosensitive transcription factors.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study sheds light on the intricate relationship between nuclear force and nucleocytoplasmic transport, revealing a general mechanism by which mechanosensitivity can be conferred to protein localization and transcription. We have demonstrated that nuclear force influences both passive and facilitated diffusion, with important implications for our understanding of cellular responses to mechanical stimuli in various physiological and pathological contexts. Our findings not only provide valuable insights into the mechanistic basis of mechanosensing, but also open up exciting new possibilities for therapeutic intervention and the development of artificial mechanosensitive transcription factors. By uncovering the complex interplay between mechanical forces and cellular processes, we pave the way for a deeper understanding of the role of mechanosensitivity in health and disease, and for harnessing this knowledge to develop innovative strategies for the mechanical control of transcriptional programs.